The British Settlement of Kenya - 2 of 4

Part 2 - development

In 1963, when Kenya achieved its independence, one of the issues the first President, Jomo Kenyatta, had to deal with was anger at the family of Lord Delamere. In 1906, Lord Delamere had come to a personal arrangement with the Maasai and took possession of the Soysambu estate at Elementeita, which is about half way between Nairobi and Nakuru, and after independence, the Masai had taken to reviling his descendants as the family who had stolen their land. Delamere’s statue was therefore moved to the estate, and the street on which it stood, which had been named after him, was renamed Kenyatta street.

For anyone interested in the history of Kenya, it’s well worth looking into Lord Delamere. He was a man of contradictions, deploying literally his entire fortune to the development of Kenya’s agriculture. He tried crop after crop, losing them to local diseases, and imported thousands of livestock animals, trying to create a breed that would both tempt rich export markets and withstand local conditions. When he died, Kenya had the most stable economy in Africa, largely due to his efforts, while at the same time, he had accrued more than half a million pounds in debts.

Delamere first came to Africa to hunt lions in Somaliland, a practice that hits modern sensibilities somewhat differently. He had a great hand in forcing the House of Lords to create the colony of Kenya, was an avowed white supremacist who fought the British government’s efforts to secure native rights, was personally friendly with a great many Masai and frequently expressed admiration for both them and for the Somali peoples he had encountered whilst trophy hunting, and was instrumental in bringing British settlers to the whites only highlands, which he himself is credited with establishing.

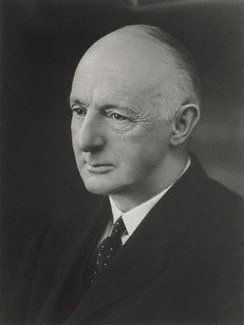

Hugh Cholmondley, Lord Delamere

These settlers, known as “The Happy Valley Set”, were notorious for spouse swapping, alcoholism, and violence. And yet, he spent every penny he had and went deep into debt to improve and develop the country in which he’d settled, and his descendants live on Soysambu estate as Kenyan citizens to this day. If you’d like to dive deeper into Lord Delamere’s complex history and legacy, you can find out more here.

As the colony grew, a two tiered society began to form. In an effort to protect native populations, the Imperial government had set up a reservation system, setting aside land for the various tribes as well as for white settlers. Pressure and lobbying from the settlers, however, had ensured that the best farming land had been set aside for whites, while overcrowding and other issues in the black reservations led to many taking work on white owned farms. These labourers were not permitted to own land in the highlands, but they were paid and often were allowed to raise their own cattle and crops.

For seventeen years from 1946 my parents owned and ran a fifteen hundred acre farm in the Rift Valley, near the village of Ol’Kalou, which means “the place of Kalu”, who was a Masai chief. They always had about thirty five families employed, mainly Kikuyu, with five Luo families. The Kikuyu all left during the ‘Mau-Mau’ emergency to be replaced by thirty families of Wakamba who were not involved in the insurgency.

Ol’Kalou

When they bought this land, just after WWII, the Kenyan government was largely dismissive of the aspirations of the local inhabitants. The farm itself was a good microcosm of how settlement went. The land had been an emergency grazing patch for the Masai, but it had been taken and declared crown land in 1910, then parcelled up and sold to speculators. This was the story of most of the high quality land in Kenya.

My parents provided rations - not just for the workers, but for their whole families. These were made up of posho (maize meal) and often the meat from the bull calves that were habitually slaughtered at birth. Each family was allowed to graze five head of cattle (no goats) and had a quarter acre to grow whatever they wanted except for bhang.

Was this some kind of Utopia? Of course not. While our resident families were better off than those in the Reserve areas, Kenya was still an unjust society with whites at the top, Indians in the middle, and the local Africans at the bottom. The Legislative Council (Legco) was made up entirely of whites elected by white settlers. Some attempt was made to include Africans in Legco but this failed miserably. Any laws passed by Legco had to be approved by the Privy Council. What this meant was that, effectively, only white settlers had full political rights, and the Indian immigrants and local Africans just had to lump it.

Given that the white population never exceeded sixty thousand, while the local population continued exploding owing to medicine, a growing economy, and being crowded onto unproductive reservations, it should have been clear to anyone that this situation, constituting a handful of incomers ruling over millions without representation and against their will, simply wasn’t sustainable. Well, it was pretty apparent to many people, but not to the Kenyan colonial government or many of their imperial masters back home.

This is where the British administration really made a mess of things. While there were significant elements of the British government and people who wanted nothing to do with empire, especially in the fifties after India’s successful independence, the bulk of the government still felt that white settlement of foreign territories was both beneficial and a sacred duty - attitudes which seem insane to most of us today. As such, the British government strongly encouraged its citizens to move abroad and arrogate large swathes of land to themselves.

Captured Mau Mau fighters

This, of course, perpetuated resentments and tensions that had been simmering since the 19th century, and as the world changed and became more connected, and native peoples began to see real pathways to ridding themselves of their colonial masters, the situation in places like Kenya became more and more untenable. My father understood this very well, and he kept a careful eye on the workers at our farm, a task made easier by his fluency in Kikuyu.

In 1949, my father noticed a meeting taking place in a tractor driver’s hut. As he listened in from outside, he realised to his horror that this was a Mau-Mau meeting - the Mau-Mau were an insurgency hell bent on the violent overthrow of the colonial government. The Mau-Mau man who had come to address the workers told his audience that they would assuredly “chase the whites into the sea”. He then collected fees from all the Kikuyu farmhands, and nominated the cook to be the oath administrator, with the house servant as his enforcer. The cook was told to recruit all the Kikuyu and make go through the violent oath ceremony particular to that people.

My father was both alarmed and devastated. Alarmed that a violent insurgency was recruiting on his property, and grief-stricken that his tractor driver, whom he liked and respected, was a part of it. He personally reported this meeting to the Commissioner of Police in Nairobi, who dismissed his concerns, poo-pooing the Mau-Mau and saying they had everything under control. History, of course, has a different view. When my father insisted on the seriousness of his news, he was told in no uncertain terms to keep his mouth shut if he wanted to avoid being in deep trouble.

Here again we can see a microcosm of British rule in my father’s estate. They had exploited and speculated, pursued schizophrenic and contradictory policies, and now, with a deadly serious insurgency brewing, they hand waved it away with spectacular blind arrogance. And all the while, good people of all colours were being inexorably forced into being players in an unfolding violent tragedy.

In the next instalment, we’ll look at the events leading up to our family’s departure from Kenya.