The British Settlement of Kenya - 1 of 4

I’ve noticed a tendency to dismiss the British Empire’s settlement of Kenya as a brutal and cynical resources grab, motivated solely by greed and racism. While greed and racism are indelibly and tragically a part of the story of British colonialism, this narrative obscures what I think are some quite important aspects of the story, some of which I witnessed personally.

While this is by no means a defence of British colonial expansion, I think it’s important to preserve true memory, like the fact that this effort was undertaken slowly and with great reluctance, and that the imperatives that drove the British had very little to do with Kenya itself.

This is important, especially given that the world we live in today seems to be imperilled by irresponsible expansionism that, if not identical to the British Empire’s, has worrying resonances. In such circumstances, it is critical that we learn the right lessons from history, which can only be done when we understand the detail and nuance of past events.

Part 1 - settlement

In the late 1850s, two men - Speke and Burton - mounted a Royal Geographic society expedition to find the source of the Nile, which Speke did, this being Lake Victoria. It’s an amazing story, involving an ex-spy, a big game hunter, and a bitter feud that simmered on even after Speke accidentally killed himself with a hunting shotgun. If you’re interested in learning more about this fascinating story, you can find more details here.

Partly because of Speke’s journeys, a British protectorate was declared in the lakes area in 1894 in a they named Uganda (land of the Baganda and Bunyoro peoples), which was created in part to protect the empire’s interests in Egypt, which relied on the Nile as a lifeline. One of the most important of these interests was the Suez Canal, which since its completion in 1869 had become one of the world’s most crucial trade routes, and a massive source of wealth for both the British and the French.

The Suez Canal

In the meantime, missionaries had settled the populous coastal strip of modern day Kenya, nominally under the rule of the Sultan of Zanzibar, and the Imperial British East India Company had been established in the inland areas, aggressively encouraging settlement into what they found to be an underpopulated and largely underused land. By the early 1890s, the company had begun to founder, and various groups, including missionaries who were heavily invested not just in Christianisation but in stamping out the slave trade and the local wars that fed it, had successfully lobbied London to take over the territory. This they did, calling the whole thing “British East Africa” and, in classic British style, paying little to no attention to the enormous ethnic disruption caused by the lines they airily drew on their maps.

Unusually for an incoming colonising power, the annexation of Kenya was achieved with little bloodshed. When the white settlers arrived they found a virtually empty country. There was no Government, no schools, no roads no hospitals, no inland cities (a depot built for the railway in 1899 grew into the city that became Nairobi), and no written language. Few, if any local inhabitants were displaced.

Against this backdrop, a man named Hugh Cholmondley (pronounced ‘Chumley’) arrived, having spent several years applying for grants of land. Cholmondley, who had by this time become Lord Delamere, acquired a huge swath of land through a combination of grants and personal agreements with the Masai tribes, and began the intensive farming practices that eventually became the foundation of colonial Kenya’s agriculture.

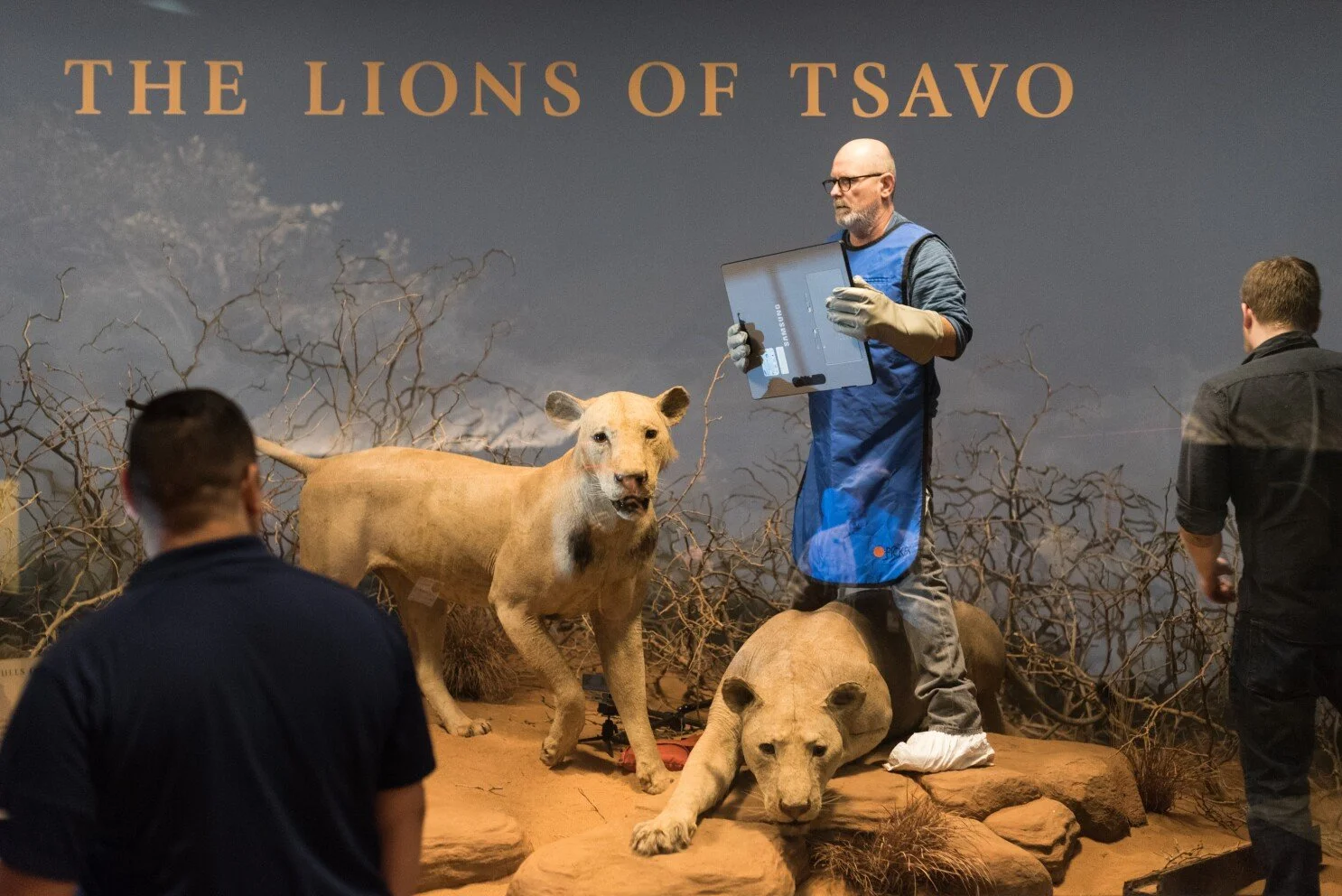

By 1901, the Kenya Uganda Railway from Mombasa to Kampala (Uganda) was completed. Nicknamed “the lunatic express” because of the cost, difficulty, and danger of the prject, the construction had involved around 30,000 workers, mostly Gujerati Indians, who were more or less forced to labour under extreme conditions of hardship, violent coercion, and famously, lion attack.

The lions of Tsavo

In an effort to protect the local population the British Government created ‘Reserve Areas’ for the forty or so tribes that lived in Kenya- these Reserve areas just took account of existing small populations- no thought was given to the future. The rest was open to white settlement and this was exclusive to whites; the local population could not own land in what became known as the ‘White Highlands”- definitely a mistake; it meant that the knowledge the new settlers brough to the country would never be used by the local population.

So the situation, by the time Kenya was reluctantly declared a colony in 1920, was as follows. A sparse native population, separated by artificial lines on the map and cut off from modern agricultural techniques and equipment were scattered all over the territory. White settlers owned all the land, and the remnants of the Gujerati workforce had essentially taken over virtually all of the retail trade in the area.

It wasn’t all doom and gloom, however. Lord Delamere’s efforts had created, after much failure and suffering, a flourishing agricultural sector, and Western medicine, which was one of the few things available to all including the natives, was mitigating or eradicating diseases that had decimated the local population for generations.

Additionally, the British Empire being what it was, they set about creating the only kind of system they understood - bureaucratic government, roads, hospitals, schools, and churches, all sustained by the railway, and mostly in service of the white community.

Over time, the hospitals and schools that the whites had built for themselves were gradually brought to the original population, with missionaries slowly increasing the uptake of education, and the locals themselves discovering the transformative power of clinical medicine. The upshot of this was a massive population explosion.

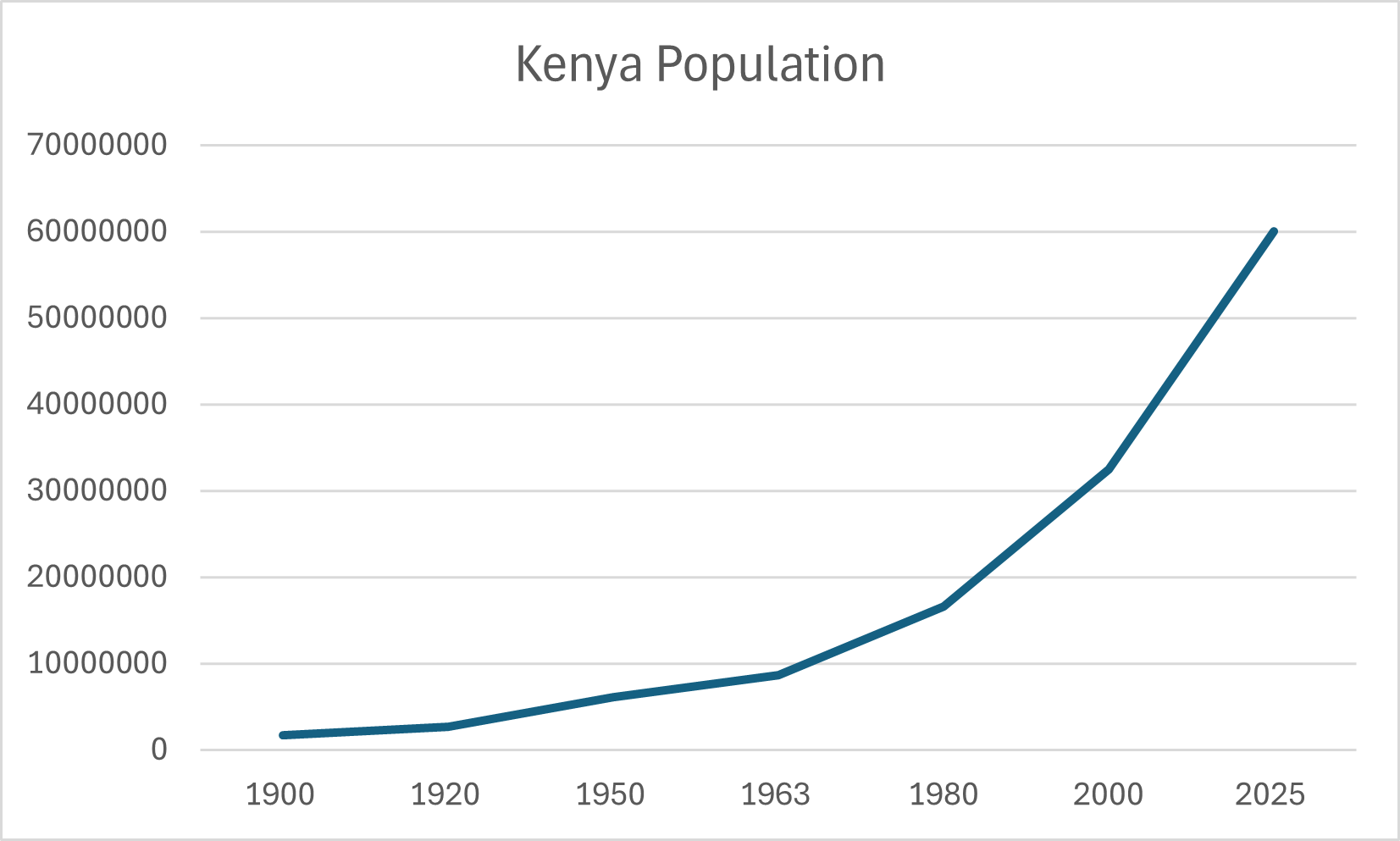

By 1900, the population of Kenya (a vast swath of territory) was a mere 1.7 million. By the time of colonisation it was 2.65 million, and by the time Kenya gained independence in 1963, it had reached 8.6 million. From there, population growth has been enormous, as shown by the chart below:

Source - UN

By 2050, the UN projects that Kenya’s population will have reached 90 million people, a staggering growth that was largely kicked off by the introduction of Western medicine, along with intensive agriculture, trade infrastructure, and the forceful repression of slavery and internecine warfare.

In the next part of our four part series, we’ll be looking at Kenya’s development.